| ABOUT | ARTICLES | FORUM | RESOURCES | GALLERY | CROSS |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Talk about this article... The Utah CIB and a Public Give-Away March 03, 2016

CLICK HERE to download this report. CLICK HERE to review the website called STOP the Uinta Basin Railway CLICK HERE to review the reports about the Community Impact Board and the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition The application to the Utah Permanent Community Impact Fund Board (CIB) for $53 million by four rural counties (Carbon, Emery, Sanpete, and Sevier) to buy a stake in a bulk export terminal (for shipment of coal and other commodities) in Oakland, California, reflects economic desperation compounded by naiveté and corporate manipulation. At the same time, the initial granting of the loan by the CIB members is an example of insufficient information leading to speculative decisions, made worse by cronyism. The desperation is a result of rural politicians seeing only the immediate economic gains that might be achieved by sustaining a declining industry. The naiveté arises from doing the bidding of outside and self-serving corporate interests. Speculation drove the county applicants to apply for the loan, but the CIB members themselves readily went along without conducting a thorough review of the plan. Coal was the commodity, but much of the speculation revolved around pretty scenarios painted for local authorities by corporate powers.

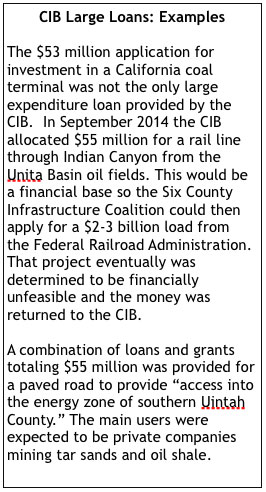

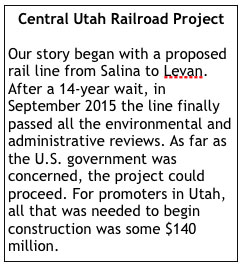

This paper describes what is known or can be implied from public documents about the processes that led to granting of the $53 million loan by the CIB. It concludes with some observations about the CIB as a public body and the limitations of its work. IN THE BEGINNING The story begins decades ago when sections of rural Utah's economies relied heavily on extraction industries, in this case coal. The more immediate beginning is in 2013 when a Kentucky-based coal company, Bowie Resource Partners, purchased three coal mines in Utah and the Utah leases of another coal company. Sufco was one of those mines, located in Sevier County, Utah, 30 miles east of Salina. Bowie is one of the largest coal mining companies in the U.S. Like other coal mining companies it has been feeling the pinch of declining coal sales in the U.S., in response to power companies switching to less expensive natural gas and regulatory controls on the burning of coal. Bowie shipped most of its coal via truck to a rail terminal in Levan, Utah, or by truck to Utah power plants. At the Levan rail siding, the coal was loaded onto rail cars, some of which traveled to a bulk coal terminal in Stockton, California, for subsequent international shipment. Up to 750 trucks a day traveled from the Salina mine to Levan. Some 1500 trucks (round trip) traveled through the town of Salina daily (1). The transport was expensive, adding to the cost of coal sales. For over a decade, Sevier County's Economic Development Director, Malcolm Nash, had been seeking environmental approvals for a rail line from the mine to Levan. He was supported in the effort by the Six County Association of Governments consisting of Sevier, Juab, Sanpete, Millard, Piute, and Wayne counties. The rail line (known as the Central Utah Railroad Project) would reduce truck traffic but even more it would reduce the costs of coal, thereby increasing Bowie's profits. Although the company had long-term contracts with U.S. buyers, Bowie looked to international markets, especially in Asia, for increased sales (2). The origin of the relationship between Malcolm Nash and Bowie executives is unclear, but they had a common interest in sustaining and expanding coal production in Sevier County. In an interview in April 2015, Nash said the permits for the rail line were nearly finalized. He is cited as saying, "When representatives of the CIB and Bowie found out about the possibility of a permitted rail project, it led them to discussion about the [Oakland] port..." (3). The rail line would be a useful transportation asset for Bowie. In October 2014, the Director of Utah's Transportation Commission, Jeff Holt, became involved in the discussions about the rail line (4). In November 2014, Holt wrote to Nash and described what needed to be done to make the case for investment in the railway (5). The following month Nash submitted an application to the CIB for $100,000 to be used to build the case for the rail line. Also in December, Holt sent Nash a draft contract for Holt's employer, the Bank of Montreal, to provide advisory services on the railway.  An example of Holt's role in arranging funding for projects comes from Huntsville in Weber County. The town wanted to increase its portion of water it shared with a neighboring faith community. The town needed money to build new infrastructure for acquiring the additional water. The Mayor, Jim Truett, reported during a town council meeting in January 2015 that CIB staff had told the town that it did not qualify for CIB funding because the county did not have industries that generated royalties for the state. However, the Mayor added, "Jeff Holt was busy behind the scenes talking with CIB board members trying to help the town." At the January 2015 CIB meeting, "the Mayor represented the Town and told the CIB board our story."According to notes of the Huntsville Town Council meeting of January 8, 2015, "The CIB board loved the story. Everyone on the committee is a chairman of a county commission somewhere, as well as heads of areas of government, two water representatives, and a UDOT person." As a result of the love-fest, the CIB board voted unanimously to grant Huntsville's request for $606,000 (7).  Jeff Holt, former Director Utah ABUSING THE CIB As the notes from the Huntsville town council meeting indicate and the minutes from the CIB meetings of January and February 2015 show, the CIB board was not adverse to advancing funding requests that staff had indicated were not permitted. Cronyism out-weighed legal niceties and appropriate review of applications. At some point in 2014, interest in a rail line for the coal mine in Sevier County overlapped with and was subsumed by interest in a proposal for shipment of coal to a bulk product terminal in Oakland, known as the Oakland Bulk and Oversize Terminal (OBOT). A former U.S. Army base was being converted to a terminal for deep-draft ships capable of carrying tens of thousands of tons of cargo. The terminal was to be developed by Phil Tagami, but required funding. We can assume that Jeff Holt became aware of the Oakland project through his position as director of the Utah Transportation Commission. A bulk terminal for coal exports would appeal to several companies and counties in Utah. By March 2015 county commissioners from Carbon, Emery, Sanpete, and Sevier counties had, at tax payer expense, traveled to Oakland for guided tours of the proposed terminal and port. Holt or a Bank of Montreal colleague organized the tours. We can also assume that prior to and during the tours a proposal was finalized for the four counties to apply to the CIB for $53 million--$50 million as an investment in the bulk terminal thereby which would buy a guarantee for priority for coal and other products from those Utah counties in shipping from the terminal. An additional $3 million was for Holt's investment employer for advisory services. JUSTIFYING LARGE CIB LOANS CIB grants and loans are mandated to mitigate the impacts of mineral extraction on local municipalities and counties. The money usually is requested for road repairs, public service buildings improvements, water and sewage systems, and planning for similar local initiatives. Most grants and loans are for under $2 million; usually, a cap of $5 million exists on combined loan/grant applications on single public service projects. CIB loans of tens of millions of dollars are justified by applicants and the board members as necessary to increase mineral extraction through infrastructure projects. The improved infrastructure, it is often argued, will increase mineral output and thus add more money to the CIB coffers. For example, in putting forward its justification for a $55 million loan for a rail line in the Unita Basin, the applicants argued that "the large infrastructure projects that the Coalition plans to pursue will be revenue producing and will increase take-out capacity for extractive industries, which in turn, will increase mineral lease royalties return to the State and given to the CIB" (8).  THE CIB LOAN FOR THE OAKLAND BULK AND OVERSIZE TERMINAL Efforts to obtain a CIB loan for investment in the Oakland terminal were moving fast. According to County Commissioner Gary Mason of Sevier County, the four counties had only found out about the proposal for involvement in the bulk port in February 2015 (9). Four counties were involved: Carbon, Emery, Sanpete, and Sevier. They expected to form an association independent of the county structures as a way to protect county tax payers from potential losses. However, the CIB had to lend to local governments or combinations of local governments, not to private associations or companies. Holt kept pushing the counties to get their act together to formalize the association, but it did not occur prior to the CIB April 2015 meeting. He did send, however, a draft contract which county governments had to run through their legal authorities. A week before the CIB April 2015 meeting, county commissioners received a preliminary Term Sheet which provided some details about the bulk port project. In his cover email, Holt wrote "Please Keep these confidential between the Counties involved (10)." Among the details in the Term Sheet were:

At its April 2nd, 2015 meeting, the CIB heard the four county request for a $53 million loan. Interestingly, Holt made the presentation, although county representatives sat at the table with him. Those representatives included: Commissioner Gary Mason of Sevier County; Commissioner Keith Brady of Emery County; and Commissioners Jake Mellor and Casey Hopes of Carbon County. The presentation emphasized the future value to Utah. It was stated that the project would be a public-private partnership (the public part being Utah taxpayer monies and City of Oakland ownership of the port). Questions from the CIB board members were primarily clarifications of the project; no skepticism or major concerns were raised. The presentation and questions and answers lasted nearly 90 minutes. The CIB board then approved moving ahead with the loan (11). The discussion at the CIB meeting gives the impression that representatives of the four counties and Holt had some background information about the project. However, it is unclear what level of detail and understanding of risks and other long-term outcomes county representatives and CIB board members had about the project. It appears that the promise of a 10 percent return on the counties' investment was a persuasive factor, but no financial analysis was presented. And early in 2015 it was widely known that coal demand in the U.S. was declining, but it was expected that demand from China, South Korea, India, Japan and other Asian countries would continue, if not increase. That latter assumption turned out to be wrong, and could be foreseen early in 2015. China's coal imports from the U.S. fell by 80% in 2014 from 2013 levels and fell further in 2015 (12). All of a sudden, U.S. coal exports were exposed to the boom-bust cycle that tends to follow most mineral commodities. The $50 million in Utah public funds was seen by the bulk terminal developer, Phil Tagami, as a critical sign to other potential investors that the project had a credible financial foundation. Tagami wanted the Utah money by June 2015 so he could work with other investors to secure the full $250-$275 million for the project. It is worth noting that Tagami is a long-time supporter, advisor and financial contributor to Governor Jerry Brown of California. Several commenters have noted that Brown's advocacy for climate change (including his participation at the 2015 Paris climate change summit) also should call for him to speak out on using the Oakland port for coal exports (13). As of early 2016 Brown had not issued a comment. IT HITS THE FAN Five days after the April 2nd CIB meeting, the Richfield Reaper reported the story (14). Sevier county economic development director, Malcolm Nash, is quoted as saying, "It's all about finding a new home for Utah's products and in our neighborhood, that means coal." Nash said that Governor Gary Herbert had verbally endorsed the project. Nash goes on to say, "The purchase of Sufco [coal mine] by Bowie [Resource Partners] is what's driving all this... "  The Salt Lake Tribune and The Deseret News picked up on the story toward the end of April 2015. Journalists in the Oakland area, too, began to file stories about the project. Oakland political leaders and citizens' groups began questioning the shipment of coal through the city and the use of the bulk terminal for coal exports (17). In Oakland the surrounding communities of the San Francisco Bay area activists began organizing in May 2015 to oppose the shipment of coal through the proposed bulk terminal. During the summer months of 2015 environmental, public health, community, and faith-based groups built public opposition. Some 10,000 signatures were collected in opposition. When the Oakland City Council held a public meeting on the proposed terminal in September, hundreds of people signed up, most to speak against coal shipments through their communities. It will not be until the middle of 2016 that the Oakland City Council issues its opinion on the coal shipments through the city to the bulk terminal. It is awaiting a report on the environmental, safety, and health impacts of moving coal through Oakland (18). However, three council members did voice opposition in the wake of the public hearing. Promoters of the bulk terminal have not been quiet, either. They have organized some faith leaders to support the project and have offered some environmental groups a small portion of the terminals profits in return for their support for the project (19). In Utah, the CIB loan had been questioned by the State Treasurer who has a seat on the board as potentially illegal and beyond the scope of CIB authority. On October 22, 2015, at the behest of several clients, the law offices of Christina Sloan in Moab, Utah, sent a letter to the Utah Attorney General, Sean Reyes, asking for a review of the CIB decision to make the $53 million loan. That was followed on November 2, 2015, when environmental, public health, and citizens' organizations in Utah and California formally asked the Utah Attorney General to find that the CIB loan violated both federal and Utah law in making the loan. In the middle of December, it was reported in the press that the Attorney General likely would not issue an opinion on the legality of the loan. It was noted that the state legislature or courts were the appropriate bodies to address the issue (20). The CIB itself says the loan is under legal review and the findings of that review will be discussed at its May 2016 meeting. Also in December, Jeff Holt resigned from his position as director of the Utah Transportation Commission, citing his transfer by his employer the Bank of Montreal to New York.  And that is where the issue of the $53 million CIB loan stands as of early February 2016. Possible outcomes that might be foreseen include:

SOME LESSONS A FINAL NOTE Two decisions will be made in the middle of 2016 which will determine, in part, whether the CIB will actually put up the $53 million to the four counties for investment in the bulk terminal in Oakland. The first decision will occur as a result of the legal review of the loan; at its May 2016 meeting the CIB will hear about the legality of the loan. Toward that end, the four counties may find that they do not have a legitimate basis for accepting the loan. The other decision will probably occur in June 2016 when the Oakland City Council considers whether to change the conditions of its agreement for the development of the bulk terminal. If the City Council determines that coal shipments through the city and from the port raises too many safety, health, and environmental issues, it may invoke its right to alter the contract to exclude coal exports at the bulk terminal. This paper will be updated as new information becomes available, especially as a result of these two decisions. FOOTNOTES

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

CIB REFORM Documents and News

Talk about this article... |

| ||||